Networks are as ubiquitous in Nature as they are in the human world. Whether we are talking about the network that is a social-media platform with its community of users and its collection of accounts, or posts, or contents, or the relationships between the employees in a large firm, or the members in a large society, or the relationships between the different species that inhabit, and form, an ecosystem, it is all about networks. In this series of posts I want to briefly give you a non-technical introduction to the language we use to describe and analyse networks in all their bewildering variety.

What are networks?

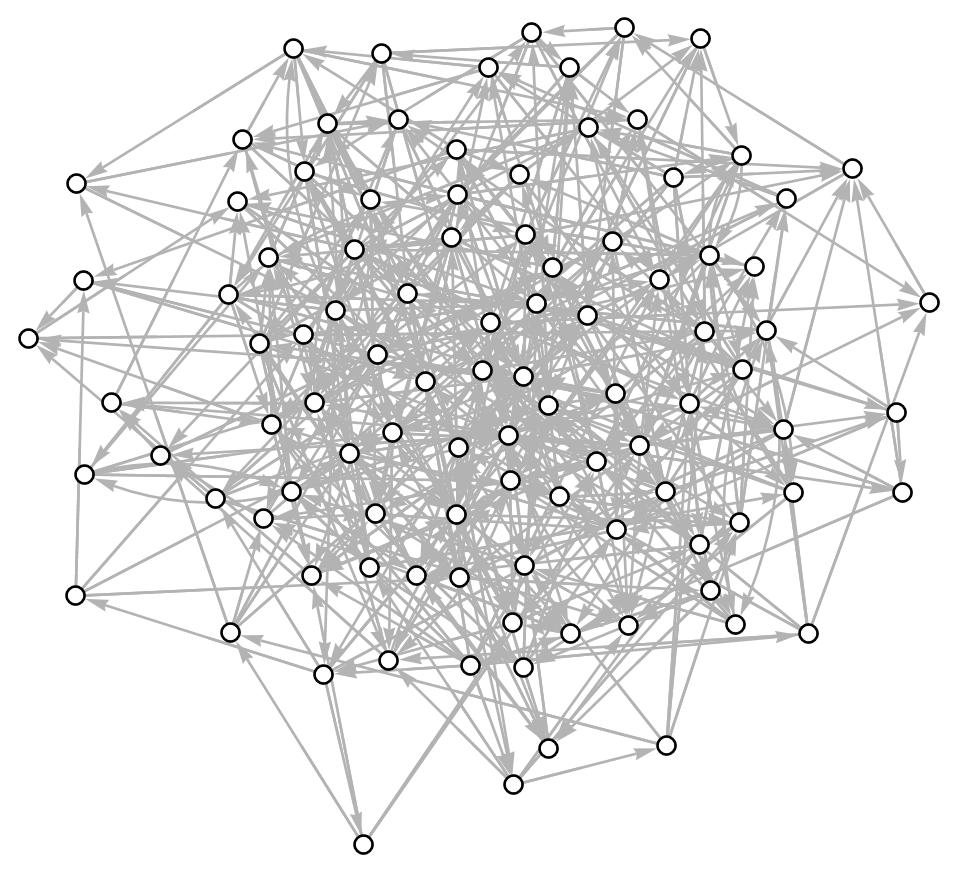

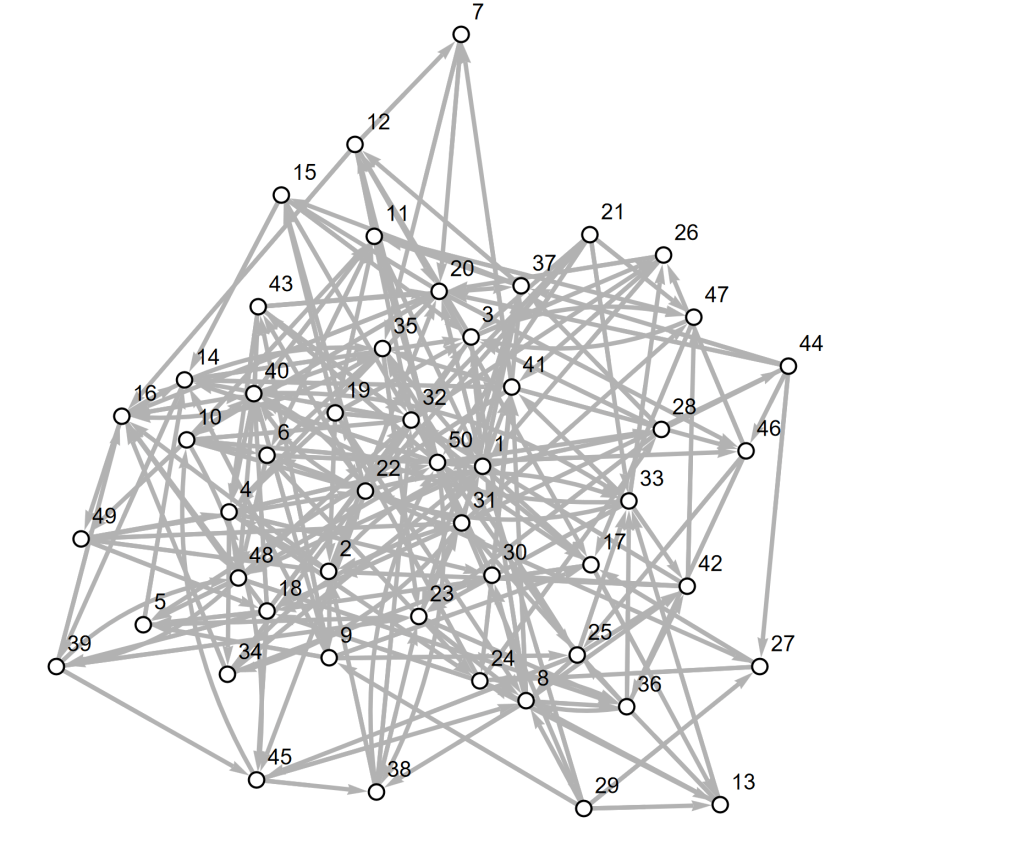

Most of us have a general idea about what networks are that is very close to the way we use this word in Sciences, Economics, Political Sciences and many other disciplines. A network consists of a set of “nodes“, sometimes also called “vertices“, and between the nodes we have “links“, sometimes also called “edges“, that usually go from one node to another. Below you can see such a collection of 50 nodes, represented by the open circles, and a collection of links that are represented by a grey arrow from the node where they start, to the node where the link ends.

The network above belongs to a special class of networks in which a link between two nodes was drawn randomly by ‘flipping’ a coin, or rolling a die, or using some other random process that gives us a fixed chance of getting a link. Networks that are created in this way are called Erdős–Rényi networks. They are an example of what are known as “random networks” and studying different families of such random networks is extremely important when trying to understand the possible variety of networks, as well as in trying to understand how some of the networks we see in the real world might have formed. Erdős and Rényi formulated their models in the late 1950’s and so you might argue that this is not a very old discipline yet and there is much left to explore.

How to talk about networks?

The trope that a picture says more than a thousand words is not really true for networks. The picture above does not actually reveal very much about how that network was created, or whether it contains any meaningful structure or regularity. Because I know I created it randomly, there is very little meaningful structure in there because for each possible link it was decided randomly, in an identical way with identical probability, and independent of whether there were any other links, whether than link existed or not.

Networks we encounter in the real world might ‘look‘ to us as if they are also without any meaningful structure, or they may on the contrary seem to display meaningful regularities, but how are we actually to decide which is which? The first problem we need to solve when we want to think about networks is: How can we talk about them?

Adjacency

In our day-to-day affairs in our life, the role of a language to deal with many things we need or do, is played by numbers. We label time in terms of numbers, for example in our age, our shopping lists are lists and columns of numbers and words, and we even express the value of a thing, like a car or a house, in terms of numbers of either units of some currency, or numbers of other units of goods or services we would be willing to exchange for that car or house. The algebra of numbers, addition, subtraction, division and multiplication, is something we are all familiar with, have learned in primary and secondary school. For most of what we do in daily life, this algebra is subtle enough to allow us to ‘talk’ about lots of things, whether it is how to divide a cookie between 3 friends, and telling you partner how much higher your body-temperature is as an indicator of how serious your fever is.

For networks this turns out to be a little more complex. If we want to use numbers to describe interesting aspects of networks, or even just the simplest aspects of networks, a single number and ordinary addition and multiplication are no longer subtle enough. Don’t worry … we will still be using ordinary numbers, but we will need plenty of them.

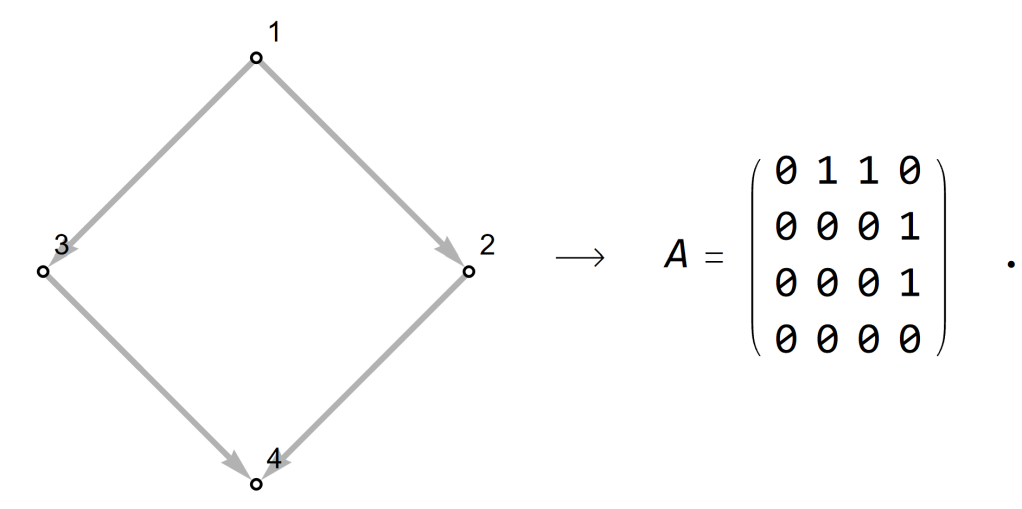

Below you see a simple network on the left, four nodes called 1, 2, 3, and 4, and four links going from 1 to 2, from 2 to 4, from 1 to 3 and from 3 to 4. On the right you see a square of numbers, and this square contains the same information as the picture on the left.

This works as follows: For every node there is a row and a column. The first row belongs to node 1 and it contains four entries. The first entry is 0 meaning that there is no link from 1 to 1 itself. The second entry is 1 indicating that there is a link from node 1 to node 2. The third entry in the first row is also 1, representing the link from node 1 to node 3. The final entry into row 1 is 0 for the reason that there is no link from node 1 to node 4.

Such a square of numbers is called a matrix. This matrix is like a small excel-spreadsheet, a list of lists, that described which nodes are connected with which other nodes. It is called the adjacency matrix of the network because it shows which nodes are adjacent, i.e. are neighbours connected by a link.

The algebra of steps

These squares of numbers have a wonderful property: they can be multiplied, added, subtracted, and sometimes even divided on each other! This is not just an algebra of numbers, but an algebra of matrices. It took humanity a few thousand years to discover this algebra. The first uses of such squares of numbers were already recorded in early China centuries BCE, in Europe their systematic study started in the 16th century, and by the end of the 19th century became part of a discipline within Mathematics known as Linear Algebra.

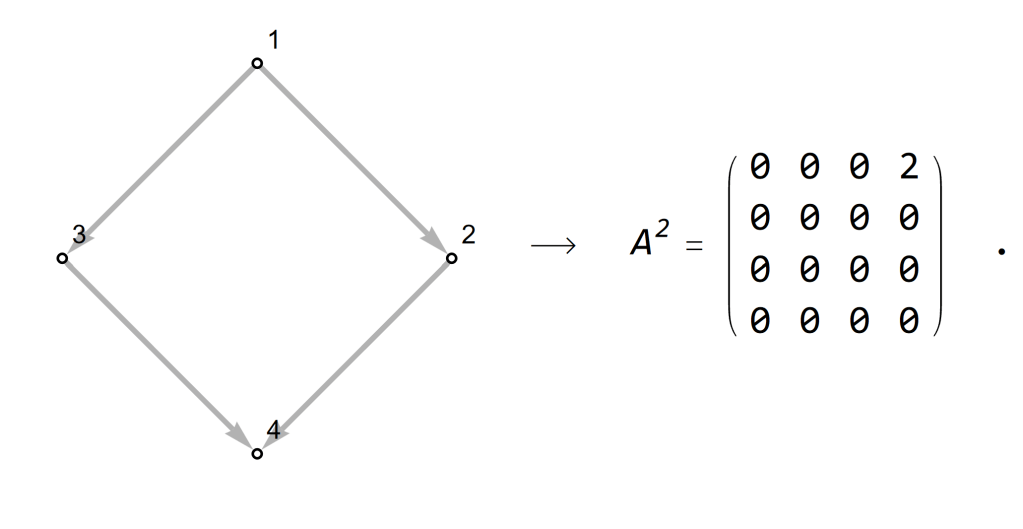

Why does that matter for us? Well, if we take the adjacency matrix A from the picture above and we multiply it with itself, we get the following:

The square with zeroes and a single 2 indicates the following: There are 2 ‘links’ from node 1 to node 4 in two steps, and there are no two-step connections anywhere else. The two-step connections between 1 and 4 are: 1 to 2 to 4 and 1 to 3 to 4. The algebra of matrices allows us to describe the links between nodes in a network, but on top of that is also allows us to calculate and study the paths in a network of 2 or more steps.

What’s next?

In this first post of this series on the Language of Networks I hope to have made it seem reasonable to you that i) we have a method of using ordinary numbers, like 0 and 1, and squares of such numbers, the adjacency matrix, that we can use to describe networks, and ii) these matrices and be multiplied with one another, or with themselves, allowing us to calculate, and count, paths through networks just on the basis of knowing the adjacency matrix.

In the next post in this series I will cover how we can describes things at the nodes moving along the links. This too will turn out to be just another application of the algebra of lists of numbers.