In the first post of this series, I wrote about the basic ingredients to describe networks and how those also allow us to study paths through networks. Now, I will turn to describing things on networks and we will see again that we can use lists of numbers to describe those, and to study how they move along paths.

Values at nodes

When you think of networks, for example a public transport network, then usually you are interested in the things on that network. In the case of a public transport network, where the nodes are stops or stations and the links are transport-connections, like in the London Tube network below.

The “things” on the network here could be passengers waiting at the various stations, or trains ready to depart from the various stations. But in principle there are very many possible things that we might interested in that are described by a number at each of the nodes.

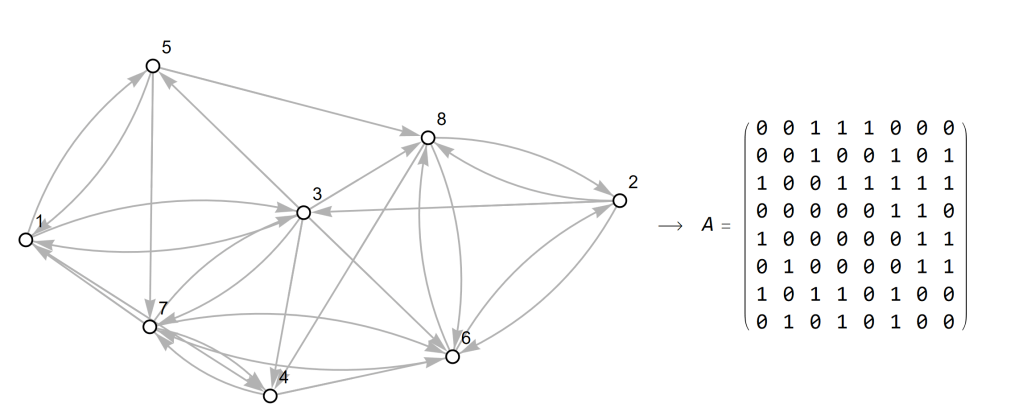

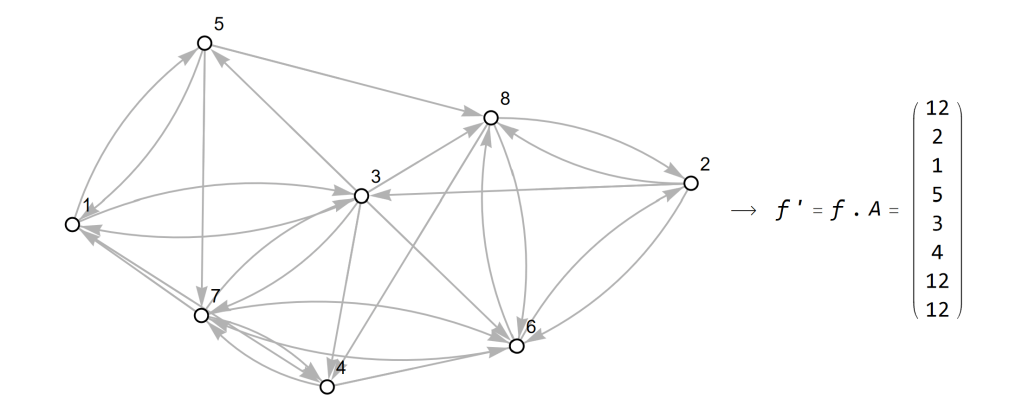

I explained in part I how we can present the information about which nodes have a link towards which other nodes by means of an adjacency matrix, i.e. a ‘square of numbers’. Below we see an example of a network with 8 nodes (the open circles) and many links (the grey arrows). From the picture on the left it is easy to see that, for example, node 5 has links going out to nodes 1, 7 and 8.

If you look into the 5th row of numbers of the matrix A on the right, you see that all 8 entries are zero expect the 1st, 7th, and 8th entries, which are 1. That is precisely the description of those three outgoing links. If you go down the 5th column you will notice that the 1’s in the column occur precisely at the spots where you would expect a 1 given the incoming links from other nodes into node 5.

Listing values at nodes

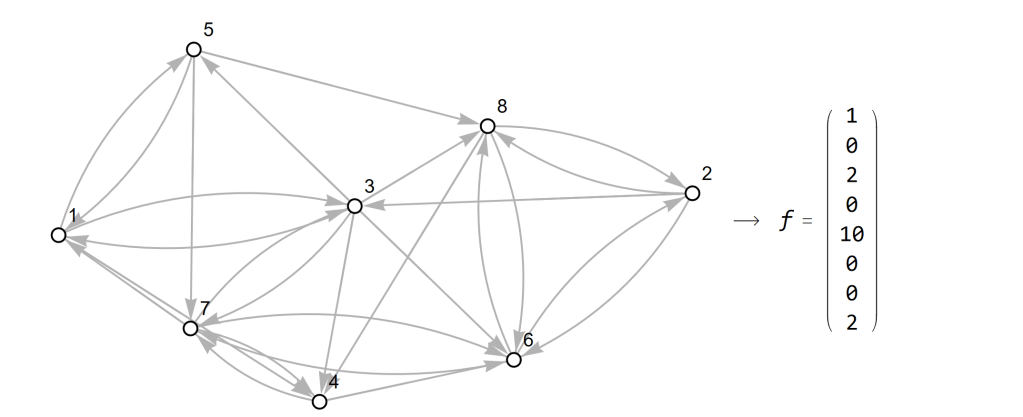

If we have a quantity we are interested in, such as for example the number of trains waiting to depart at each node, in a transport network, then we would simply describe this by a list of numbers. Suppose that our network is a messaging network where at each node there is a computer that takes all the messages it has received at some time t and forwards them to all the nodes it has an outgoing link to, at time t+1. This is basically what Email-servers do.

In the network below, I have assumed that node 1 has 1 message node 3 has 2 messages, node 5 has 10 messages and node 8 has 2 messages waiting to be sent onwards. The list of the number of waiting messages at each node is called f in the illustration below, on the right.

Now wouldn’t it be nice if there was some simple way of calculating how many messages there are at each node at t+1 when all messages waiting at time t have been forwarded. It turns out, there is indeed a simple way of doing so. Last time, we saw that multiplying the matrix A with itself allowed us to calculate how many two-step connections there were between each of the pairs of nodes. This time, it is the multiplication of A on the left with f that generates the correct answer.

For example, node 1 now has 12 messages, because even though it has forwarded the 1 message it had earlier it has received 10 messages from node 5 and 2 messages from node 3.

How do we do the multiplication?

I haven’t explained how we multiply such lists with such matrices, I have only said that we can do so and that it gives the correct results. I also didn’t explain in the previous post how we multiply two matrices together. My aim with these posts is to keep them as non-technical as I can. So, if you are happy to accept that there is a systematic way of doing such multiplications then that will be all that you will need to be able to follow the future posts in this series.

If you would like more detail about how to do such calculations, then let me know in the comments! I will be happy to start a separate series on the more technical aspects. They are not very difficult, and matrix-multiplication is a standard part of the first-year of mathematics, physics or economics degrees, and in many countries it is also introduced in the final year of secondary school mathematics. For this series of posts however, how to do so is not as important as why we do so.

Multiplying lists of values, like f, by matrices, like A, is a very convenient description of how ‘things’ might move along networks.

Spreading a disease

A classic example of where we use these mathematical techniques, is in studying how a infectious disease might spread through a population. In this example, the nodes would be people, and the links would represent the social interactions these people have with each other during a working-week day. We could assign to each person a value of how many (if any at all) viruses they carry at some time t, and we would have a matrix W that contains numbers describing how likely it is that an infected person (node) will infect another person (another node) via the social interaction they have (the link) that day. The list of infection-values I at time t will then be updated as follows for the next day t+1: I‘=I + I . W where the multiplication describes how the infection spreads through the network of people.

‘Lockdowns’ are a public-health intervention that aims to reduce the number of social interactions, i.e. to change / reduce the numbers in the matrix W. These kinds of models are difficult to work with because we are usually dealing with a very large number of people (many nodes) and a complex set of interactions (many links) that also might change from day to day, or change between work-days and weekend-days. But multiplying long lists, or large squares, of numbers is something that computers are very good at.

Next time

I hope that this post has shed some light on how squares of numbers and lists of numbers are extremely useful in describing networks, and for describing processes that happen on networks, such as sharing messages on a messaging network, or spreading a disease in a network of social interactions during day-to-day life.

In the next post I will have a look at a tool that allows us to study differences across networks, for example when dealing with a network of people who are each earning some income then an economist studying that network might be interested in describing the differences in income between people who are connected by a link of some kind.