Watching discussions about Mathematics in primary and secondary education, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world take on ever more absurd intensity, inversely proportional to the value of the math actually taught, we see politics-driven didactics that destroy mathematics every bit as much as it destroys the humanities. And folks just sit, watch and nod it on.

Who am I to say so?

As a kid I went to primary school in a small rural town almost on top of the Dutch-German border, in the ’70’s. Even as late as the 1990’s the nearest motorway, about 10 miles away, still carried a warning sign saying: “No petrol stations for the next 70 miles“. The roads on both sides of the border, in the ’70’s, were dead-ends. There was a border, with border patrols, there was smuggling of coffee, petrol and cigarettes. The local farmers would hunt in the local forests, incomes were low, religious, sectarian, divisions were deep. There was a catholic primary school, an orthodox protestant one, and a ‘public’ one.

We threw rocks at each other, kids from mine were called heretics by the kids of one, and heathens by the kids from the other. A few of my classmates had parents who were functionally illiterate, at least one of my classmates was received life-changing injuries when helping on the family farm in the harvest season. How was I, as a 6-years, old to understand that in this school I would learn 2 lessons that I still remember to this day, and whose impact on me was only comparable to things I would learn almost two decades later when at university.

One of those lessons, that struck me deeply as a 9 years old although back then I would not have been able to verbalise how or why, was a history hour. I still have the image of the moment burned into my memory, as fresh as it was on that day, and I tell myself I can actually still recall the feelings of that moment. My shortly-bearded, 30-something, rather strict and inquisitive, year-4 teacher stood in front of a poster depicting Emperor Napoleon crowning himself. He passionately encouraged us to see that act as a deliberate mockery aimed at all crowned heads in surrounding Europe … and something ‘clicked’ inside my head.

Something similar had happened 2 years earlier, but now in my arithmetic class in year-2. Of all places in the world, this little school, in this little village, had a female year-2 teacher who was into “New Math“, the much derided innovation in mathematics education, originating in the US, that was a hype for a decade or so in the late 60’s and early 70’s. Not only was she a relief, after the year-1 teacher who had a habit of physically disciplining unruly kids in class, she also introduced us to set-theory. Her contribution to my mathematics education, and to the joy I took in learning it, would remain unmatched until I went to university. I guess living in an impoverished border-town full of sectarian divides makes an understanding the principles of set-theory and the operations of taking unions and intersections all the more relevant. For me, it had been pretty much the only bit of maths I had understood, that had felt worth understanding to me, and that was taught in a way that made me feel someone actually cared whether I understood or just ‘followed rules‘. For years, that moment remained in my mind, making a mockery of almost all of the subsequent mathematics teaching I suffered through and performed poorly under.

Years later, my first lecture, on my first day in university, was an Analysis course taught by the late Dutch mathematician Hans Duistermaat. One of his first sentences in that lecture was: “Forget everything you have learned so far! We are going to start all over again!” I felt a great sense of relief, as I hadn’t understood much from the years between that primary school time and and now. I had jus about managed to “function follow rules” enough to get into college. A struggle that had taken two years more than it should have … but that was something that ran in my family.

Maths taught-to-the-test

Much of the criticism that were aimed at the “New Maths” were most likely probably correct. Based on my own experience as a primary school kid, but even more so as a lecturer in rather mathematical subjects such as theoretical physics and, since 2010, economics, there was something fundamentally correct about what “New Maths” was aiming to do despite it not having been done well at the time. When the approach was discarded, much more was discarded that just a failed attempt. What mathematics in primary and secondary education has become since then is little more than a zombie-version of the subject. This is not because of a single culprit, but it is because of the role this maths was assigned increasingly, in particular in the US and UK, but not just there. The underlying disease not just eats away at mathematics, but also at the other sciences, and at languages and the humanities in general.

In countries where modern foreign language are still taught as a matter of obligatory content, these subjects have been largely turned into pure ‘skills’ courses quite inefficiently drilling “just follow the rules” into kids minds. From my own secondary school drill in languages I hardly remember anything, although I will never forget the two weeks my class (and parallel classes) spent, in 1981, on Ionescu’s “Rhinoceros“. Although much of it went completely over my 15 years-old head, listening through the three acts and having the teacher discuss them with us … is something about which I sometimes still pinch myself wondering whether it really happened.

For most of primary and secondary education everything was about teaching the standardised material neccesary for centralised exams were we were invited to display how well we had internalised producing standardised answers to standardised questions about standardised knowledge and skills. When I entered university, that first day of classes I naively thought, it couldn’t possibly get any worse than my cohort had experienced, despite the fact that many had done quite well through it. There was a general acceptance that this was what it was and that, even when it was an utter waste of time and talent, … that was simply neccesary. But at university it became clear to me that at primary school my year-2 teacher, my year-4 teacher, and the French section at my secondary school had been right all along. That instead of being a dysfunctional twerp who simply couldn’t bring up the discipline neccesary to learn what mattered, I had actually figured out too early what mattered at an age where I still struggled to put that in words.

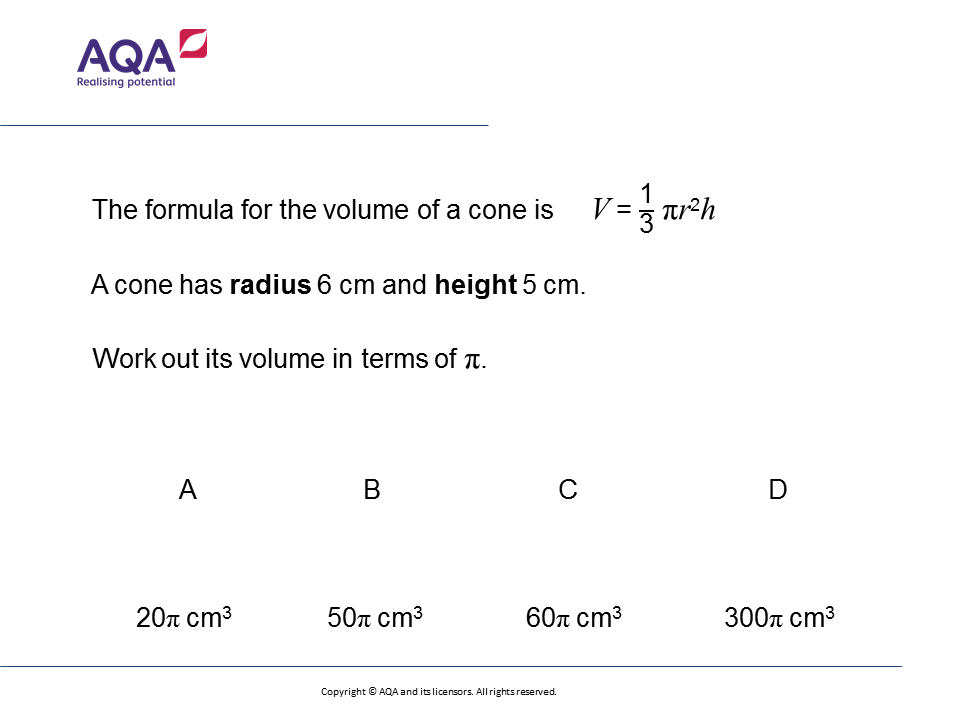

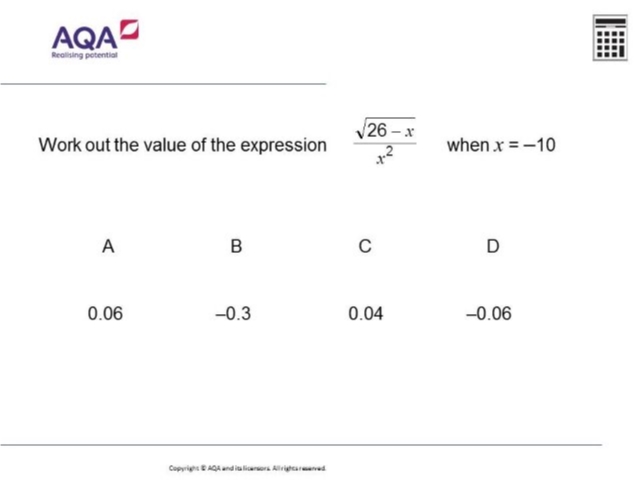

Maths gcse’s

When I moved in 2010 to the UK, I was introduced not just to the way these maths gcse’s are discussed here, but my youngest daughter was also going through them. It was dispiriting to see that not only, compared to my own experience, things could get worse but that here they definitely also had. Instead of encountering a public debate to save secondary education from this abysmal state, the debate was essentially solely about how we could possibly still make it worse. When a couple of years ago my university decided to no longer require a C in a modern foreign language at GCSE, the reality was that language teaching had degraded to a degree that such a demand became ‘exclusionary’. Of course the move was justified, even applauded by some, by remarking that requiring kids in a European country to learn a modern foreign language, which frequently turned out to be French, Spanish or, god forbid, German, was inherently imperialist and classist.

While languages and humanities slowly but surely whither away in an educational landscape that claims to be all about access, (economic) ambitions, (economic) aspirations and (economic) self-realization, and making the most of your (economic) talents, mathematics is being used as the safe-guard so that none of this could actually make any difference to who gets access to which kind of careers. We read nonsensical stories about how doing well at gcse maths is a “predictor” for getting into high-paying careers. By that logic “being male” is also a “predictor” for earning higher wages and should probably be taken as an indication we should convince more people to become male? Where the humanities have withered, maths has become the supply of standardised tests that will allow the better-off to privately tutor their kids into the well-paying careers under the banner of “meritocracy” while all they really learn there is “to just follow the rules”. No one seems to care whether they actually understand any of it, because the dimension of “understanding” has been replaced with the dimension of “getting an A*” and if too many get an A* then this is “grade-inflation” and thus a problem! Education no longer is education, but an artificial race where kids are trained to chase a fur on a stick.

Epilogue

I have encountered many physicists over the years, in my ‘old’ life as a physicist, who saw little use in requiring school kids to complete the secondary school physics curriculum because it taught them so little of the forest of the natural world of stars, elementary particles, ocean currents and climate through the trees of trivialised, recipe-based, problems wit answers that can be machine-marked (but humans do it coz cheaper). Since switching to economics, in 2010, I have talked to many economists saying the same about secondary school-level economics. Every year, I see first-year students come in with little to no understanding of the mathematics they have learned, despite earning A*s. Every year I see the societal elites patting each other on the back about what a great meritocratic system we have built here.

I feel indebted to that one courageous primary school mathematician experimenting with a new approach to things, that soon after was rolled back, one insightful primary school history-enthusiast who thought farm-kids deserve to know stuff, one small group of French teachers in secondary school who thought at 15 we could handle a fictional portrayal of a world we would want to avoid living in. I am saddened by how rare that is in the public debate, which seems ben on pushing GCSEs and A-levels become even more of a programme put together for a meritocracy of rhinoceroses, not education.